The comings and goings at Greenland’s new international airport in its capital Nuuk look a bit different of late, as journalists like me come here to see what all the fuss is about.

The fuss, of course, is the result of US President Donald Trump’s interest in taking control of the massive island that is geographically part of North America but legally is part of the Kingdom of Denmark, a member of NATO, the European Union, and a US ally.

I wanted to drill down on what’s here, what makes it attractive and whether the local population is welcoming or hesitant about being in Trump’s sights.

“Greenland is the front door for North America,” said Tom Dans, leaning into the arguments of Greenland’s importance to US national security.

I’d wanted to speak to Dans, a private equity investor with prospective interests in the Arctic who campaigned for Trump, but I hadn’t expected to see him at the airport.

To be fair, Dans wasn’t hard to spot. He’s a tall Texan with one of those wide shiny smiles wealthy Americans tend to have. He was also wearing a baseball cap emblazoned with the American flag.

He didn’t have more time to chat then, so I stepped outside, into the 14 Fahrenheit (-10 Celsius) cold that was, I would learn, balmy compared to what was to come later in the week.

“You are here because Trump,” remarked a woman waiting in front of us. Not yet accustomed to the Nordic tone, I couldn’t quite tell if this was meant as a simple statement or an accusation. “We are,” I dutifully confirmed.

“They want more tourists to come here, they need to get more taxis,” she said. We needn’t worry too much though, she explained, we wouldn’t be waiting in the cold for too long. Despite the apparent shortage of taxis, they can’t go very far and return quickly. The trip to the center of Nuuk from the airport is about 4 miles — and then the roads just stop. There is nowhere else to go, at least by car. Greenland — three times the size of Texas — has only about 56 miles of paved roads.

She introduced herself as Lisbeth Højdal, a consultant from Denmark who was here to run a course training career counselors.

The Danish government provides Greenland a grant of about $500 million every year to support health, education and other services here. Højdal’s course was part of that package of support.

So, before I’d even had a chance to look around, I’d heard the views of outsiders — one American, one Dane.

But Greenlanders have many different views.

“We have always been told that Denmark is the big savior of Greenland,” Qupanuk Olsen recalls. The Danes, she says, look down on her and fellow native Greenlandic people who are Inuit: “You guys cannot stand on your own feet; you guys don’t have anything without us. You can’t study, you don’t have health care, you have nothing without us.”

Olsen is known as “Greenland’s biggest influencer” with more than a million subscribers combined across YouTube, TikTok and Instagram where she shows the world the best of Greenlandic, and specifically Inuit, culture.

For an introduction to that culture, she brings me to see the “Mother of the Sea” — a striking stone sculpture on Nuuk’s rocky coast, depicting Sedna, the goddess of the sea in the Inuit religion. At high tide the statue is partially submerged.

Inuits (sometimes incorrectly referred to as “Eskimos”) make up almost 90% of Greenland’s population of 57,000.

We walk a few steps away from the shoreline and the “Mother of the Sea,” and Olsen points to the top of a hill and another figure, “I really want this statue gone.”

The statue, which looks over all of Nuuk, is of Hans Egede, an 18th-century Dano-Norwegian missionary who brought Christianity to the island.

“Why should he be up there? Why isn’t it a Greenlander up there?” Olsen asks. “We Greenlanders should be more proud of who we are … not celebrate some foreigner who came here and changed our culture and colonized us.”

Danish control of Greenland dates to the time of Egede. Greenland was granted home-rule in 1979 and, after a referendum in 2008, the island was allowed more self-governing powers including the ability to hold a referendum on independence (though independence would also require approval from the Danish parliament.)

But despite the increased autonomy, for Olsen the statue of Egede is a daily reminder of Danish colonization — something she purposefully talks about in the present tense.

“I used to be a royalist. I used to look up to the Danish people and thought they were better than me. Now, I’ve really realized that’s not the case,” she says.

She points to abuses of Greenland’s native people.

In the 1960s and 70s, doctors placed IUD contraceptives in young Inuit girls without their or their parents’ consent as a means of population control. An investigation by Danish and Greenlandic officials into what has become known as “the spiral case” is expected to finish this year.

“I should have a lot more cousins,” Olsen says.

Another practice known as “legally fatherless” allowed Danish men who impregnated unmarried women in Greenland to skirt any responsibilities for their child. Olsen says her mother was one of the “legally fatherless” children born here.

In recent weeks, Denmark has announced a boost in Arctic defense spending and the Danish king revealed a new design for the royal coast of arms, making far more prominent the symbols for Greenland and the Faroe Islands (also part of the Kingdom of Denmark.)

But it’s too little, too late, says Olsen, who supports independence for Greenland and is standing in upcoming elections.

She acknowledges an independent Greenland would need to sign new agreements with other countries for defense of its 27,000 miles of coastline, and other arrangements when it comes to trade and financial support, but for her that’s no reason to jump from Danish control to American.

“Why should I? I’m so proud of who we are as Inuit,” she says. “Why should we just be taken by another colonizer?”

The US already has strong connections with and interest in Greenland.

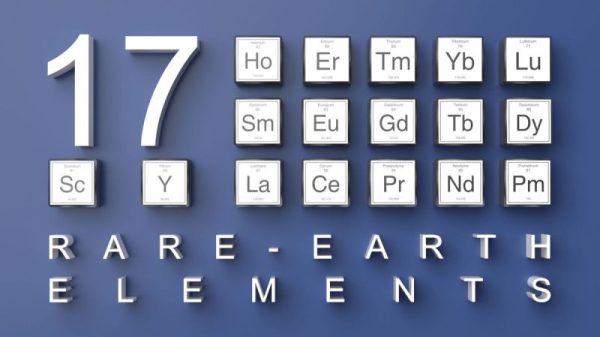

Climate change and the loss of sea ice is opening up new shipping routes between the US and Europe; Greenland is rich in oil and gas as well as rare earth minerals needed for modern development — a market currently controlled by China. A US base inside the Arctic Circle in the far northwest of the island gives the US Space Force “Space Superiority,” the military says.

For Tom Dans, the tall Texan with the wide smile, the logical next step is for Greenland to come even closer to Washington.

As we walked along the pier at Nuuk’s frozen harbor — where fishing boats with reinforced hulls, some equipped with harpoons for whaling, broke through the ice — I asked him if we were in the 51st state of the US.

“I don’t think so. This is Greenland,” Dans said, before adding with a laugh, “If we were in Canada, perhaps.”

Dans has no current role in the Trump administration, but was appointed to the US Arctic Research Commission, an independent federal advisory committee, during the first Trump term. He says he’s set up “American Daybreak,” which he describes as “a nonprofit working to build US-Greenlandic relations.”

He also has a personal connection to Greenland. After the Nazis invaded Denmark during World War II, the US stepped up to help to protect Greenland, and Dans’ grandfather was part of that effort as a merchant mariner.

When we met, Dans had just traveled to Narsarsuaq, near the southern tip of Greenland, to commemorate the anniversary of the Nazi torpedoing of the US Army Transport Dorchester with the loss of almost 700 lives in 1943.

Dans gestured toward a Danish Royal Navy vessel moored in the harbor. The Danes provide some security for Greenland but in reality, their navy is too small and the United States is again the main force protecting the island, he said.

It’s an argument he’s also made on the show of a former Trump adviser, Steve Bannon. “Part of what is really important today, in the moment, is for Americans and the rest of the world to realize how closely intertwined our country has been with Greenland for so long and why it’s so important,” he said in a live appearance from Narsarsuaq last Tuesday.

Dans brought me to a café to meet Jørgen Boassen, a Greenlander nicknamed “Trump’s son.”

Boassen achieved semi-celebrity status in the MAGA universe as Greenland’s biggest Trump supporter and was among those who welcomed Donald Trump Jr. when he visited Nuuk last month.

He has made multiple trips to the US in recent months — attending the Trump victory party in Mar-a-Lago on election night and the inauguration. And just a few days into the new Trump administration — Boassen, Dans, and a Greenlandic politician visited the White House, where they posed with the Greenland flag.

But even Boassen does not want Greenland to be taken over by the US.

He doesn’t want to be subsumed as the 51st state, he says, but wants the US to be Greenland’s “best and closest ally with everything — with defense, mining, oil exploration, trade, everything.”

Not all Greenlanders want to break free from Denmark.

“We might be ready someday, but not today, not tomorrow,” says Aqqalu C. Jerimiassen, the leader of Atassut, a party in favor of staying within the Danish kingdom.

He acknowledged the wrongs committed against native Greenlanders and said the Danes must accept responsibility.

“Every colonizer has made mistakes,” he said. “But we cannot live in the past.”

Atassut, which describes itself as a “moderate conservative” party, supports universal health care, free education, and other forms of welfare that are basic concepts across much of Europe, and which Denmark provides for Greenland.

He says while some here “very much would like to be US citizens and would like to follow the American dream,” most would not be in favor of joining the United States and losing universal access to these services.

Greenland is holding elections next month that may reveal more about its population’s views about future relationships with the world. And the parliament just fast-tracked a law banning foreign political funding.

That’s fine by Højdal — the Danish guidance counselor I met at the airport — who said Greenland’s future is for Greenland, not anyone else, to decide.

As she watches the news coming from the United States of the hectic first weeks of the second Trump administration, she says a Turkish proverb comes to mind.

“When a clown enters a castle, he doesn’t become a king. The castle becomes a circus.”

Greenland, she hopes, doesn’t become a circus.