In January 1988, one of Taiwan’s most senior nuclear engineers defected to the United States after passing crucial intelligence on a top-secret program that would alter the course of Taiwan’s history.

Colonel Chang Hsien-yi was a leading figure in Taiwan’s nuclear weapons project, a closely guarded secret between the 1960s and ‘80s, as Taipei raced to develop its first nuclear bomb to keep pace with China.

He was also a CIA informant.

Chang exposed Taiwan’s secret nuclear program to the United States, its closest ally, passing intelligence that ultimately led the US to pressure Taiwan into shutting down the program – which proliferation experts say was near completion.

“I decided to provide information to the CIA because I think it was good for the people of Taiwan,” said the 81-year-old. “Yes, there was political struggle between China and Taiwan, but developing any kind of deadly weapon was nonsense to me.”

Chang’s story bears similarities with that of Mordechai Vanunu, the Israeli whistleblower who famously exposed his country’s clandestine nuclear program to the world. But while Vanunu went public with his country’s progress, Chang’s whistle-blowing was done in secret and without any fanfare.

Taiwan’s nuclear ambitions

In 1964, just 15 years after the Chinese civil war ended with communist victory, leaving Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalists controlling only Taiwan, Beijing successfully tested a nuclear weapon – deeply unsettling the government in Taipei which feared it could one day be used against the island.

Two years later, Chiang launched a clandestine project to lay the technical groundwork for nuclear weapons development over the next seven years. The Chungshan Science Research Institute ran the project under the Defense Ministry, and it was there that Chang began working as an army captain a year later.

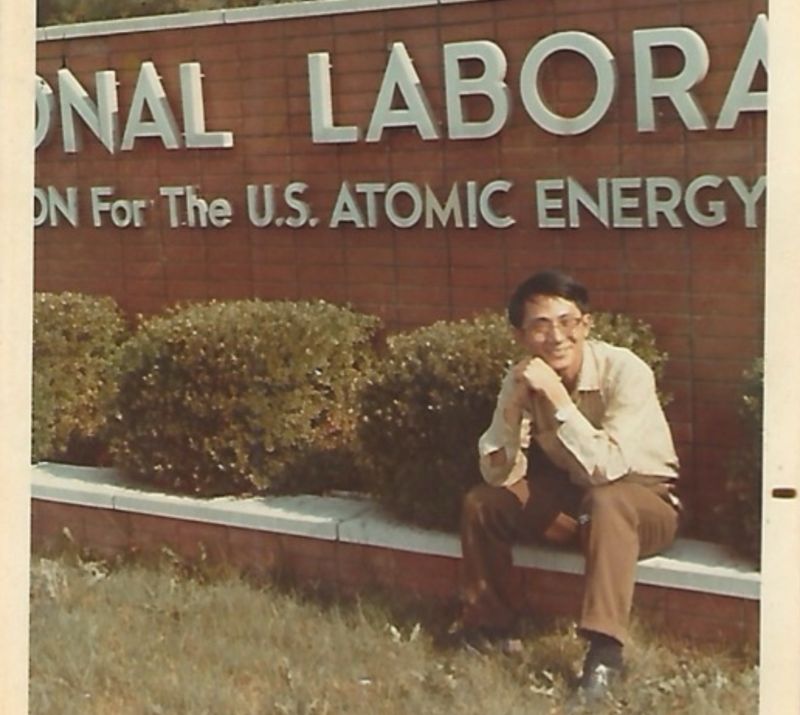

He was picked for advanced nuclear training, which would involve stints in the US. After studying physics and nuclear science in Taiwan, he attended Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee.

Despite Taipei’s official statements that its nuclear research was only for peaceful purposes, Chang said students sent to the US were all aware of their true mission: learning skills for weapons development.

“We know precisely – even though it’s not in the written statement – we know what we are going to do, what kind of area we should concentrate on,” Chang said.

“We were kind of excited and trying to get the job done,” he added. “All we did was focusing on the area they assigned us, we put all our efforts to do it, to learn as much as possible.”

While he was at Oak Ridge, Chang recalled, the CIA already had an interest in him.

“In 1969 or 1970, I remembered receiving a phone call,” he said. The caller said he was “with a company and they are interested in the nuclear power business… they offered to take me out for lunch.”

“At that time, I said I had no interest because I had a mission-oriented assignment. But I was not aware he was from the CIA; I only knew that after quite a few years.”

American suspicions

In 1977, a year after attaining a PhD in nuclear engineering from the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, Chang returned to Taiwan. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and spearheaded the development of computer codes for simulating nuclear explosions at the Institute of Nuclear Energy Research (INER), a national laboratory that covertly advanced weapons development under civilian pretenses.

Taiwanese leaders faced a delicate balancing act: the United States strongly opposed new nuclear weapons programs anywhere in the world, and Taipei could not afford to alienate its most crucial ally. The US has long relied on nuclear deterrence as part of its broader strategy to counter China’s stockpiling of nuclear warheads. But, under a policy of nonproliferation, it opposes any country newly developing nuclear weapons.

Back then, Taiwan was not the wealthy and vibrant democracy it is today. It was a developing economy under the autocratic rule of the Chinese Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang. That regime continued to hold a seat at the United Nations until 1971, and maintained formal diplomatic relations with the United States until 1979.

To minimize the risk of its nuclear ambitions being exposed, the island only sought to secretly establish the capability to produce nukes quickly at any time, but not build a stockpile.

“Taiwan’s cover stories were unbelievably good,” said David Albright, a nuclear proliferation expert and author of “Taiwan’s Former Nuclear Weapons Program: Nuclear Weapons On-Demand.”

“They always emphasized that the research was only for civil purposes… (US) officials didn’t know how to breach this cover story.”

But the risk of a cross-strait nuclear conflagration weighed on Chang. Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, who assumed power in 1978, warned that if Taiwan acquired nuclear weapons, China would respond with force.

“I think they’re quite serious,” Chang added. “I believed in that.”

“I didn’t want to have any conflict in any way with mainland China,” he said. “Using any kind of deadly chemical or nuclear weapons… it’s nonsense to me. I believe we are all Chinese and that doesn’t make sense.”

So when CIA agents approached Chang again during a trip to the United States in 1980, he agreed to speak.

“They said, ‘We know you, and we’re interested in you,’ and we had a conversation,” Chang said, adding that the Americans put him through a “very thorough” lie-detector test to ensure he was not a double agent. He assisted the CIA with some ad hoc tasks before becoming an informant in 1984.

For the next four years a CIA case officer, identified only as “Mark,” met with Chang every few months at safehouses around Taipei, including a condo near Shilin Night Market – one of the island’s most famous street food destinations.

In those meetings, the CIA asked him to corroborate intelligence, share information about recent projects at INER, and take photos of sensitive documents.

“All those conversations were quite professional. He would take a pencil and notebook to write down my answers,” Chang said. “He kept saying that they will try their best to keep me and my family safe.”

The Chernobyl disaster in 1986, a catastrophic nuclear accident in Ukraine that exposed hundreds of thousands of people to harmful radiation, solidified Chang’s conviction that halting Taiwan’s nuclear weapons program was imperative.

That same year, Vanunu publicly exposed details of Israel’s clandestine nuclear program, handing what he new to the British media and causing an international sensation. He was later kidnapped by Mossad agents, returned to Israel and prosecuted, spending years in prison.

A new chapter of life

Chang’s life – and those of his wife and three children – took a dramatic turn in January 1988, when the CIA exfiltrated them to the US.

By then, President Ronald Reagan’s administration had amassed sufficient evidence and seized the opportunity created by the death of President Chiang Ching-kuo – Chiang Kai-shek’s son – to pressure his reformist successor Lee Teng-hui into cooperation.

Albright, the expert and author, said Chang was the most crucial informant in arming Washington to shut down the Taiwanese program.

“The United States had been in a cat-and-mouse game with Taiwan over its nuclear program for years,” he said. “Chang really made sure the US had heavy evidence that Taiwan couldn’t deny… and directly confront the Taiwanese.”

In the months after Chang’s departure, the US sent specialists to dismantle a plutonium separation plant – a facility designed to extract nuclear materials for weapons production. The team also oversaw the removal of heavy water, a substance used as a coolant in nuclear reactors, and irradiated fuel, nuclear fuel that can be reprocessed to extract materials for nuclear weapons.

Hero or traitor?

To date, Chang’s decision to work with the CIA has remained controversial in Taiwan, which in the intervening years has continued its massive industrial and economic expansion, becoming a full democracy in the 1990s.

But cross-strait hostilities persist. Taipei has come under growing military pressure from China, which now has the world’s largest military and is becoming more assertive in its territorial claims over Taiwan. The Chinese communist Party has vowed to take Taiwan by force if needed, despite having never controlled it.

Beijing dwarves Taiwan’s military, spending about 13 times more on defense. Some have argued that if Taiwan had successfully acquired nuclear weapons it could have served as an ultimate deterrent – paralleling Ukraine, where Russia might not have invaded if Kyiv had retained its Soviet era nuclear arsenal instead of giving it up.

Some Taiwanese have criticized Chang, saying he overstepped by deciding unilaterally that the island is better off without a nuclear deterrent.

“I believe he is a traitor,” said Alexander Huang, an associate professor in strategic studies at Tamkang University, because the weapons “would be seen as a useful tool in bargaining for a better diplomatic result” with Beijing.

But Su Tzu-yun, a director of Taiwan’s Institute for National Defense and Security Research, said the lack of a nuclear option has not overly affected Taiwan’s modern defense capabilities, because precision ammunition can be used to achieve similar objectives to those of tactical nuclear weapons.

“The Taiwanese government back then thought that if China landed in Taiwan, it could use tactical nuclear weapons to eliminate the landing troops,” he said. “But in their absence, we can also employ precision weapons like missiles to replace them.”

Taiwan buys these weapons from the US, which – despite shutting down the nuclear program – remains its key military partner, supplying ammunition, training, and defense systems.

Besides weaponry, the island has what some consider a more effective deterrent than nuclear bombs. In 1987 – just one year before the nuclear program was shut down – tech entrepreneur Morris Chang founded the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which now produces an estimated 90% of the world’s super-advanced semiconductor chips for tech companies, including Apple and Nvidia.

The island’s integral role in the global semiconductor supply chain, some observers say, would be enough to deter China from launching an invasion, forming what is dubbed its “Silicon Shield.”

Albright, who conducted extensive research into the Taiwanese program, also said its success would not have been beneficial to Taiwan.

“I think [it] would have raised the military risk of a Chinese attack,” he said, while Washington could have also responded by “reducing its security commitment or limiting military aid” once Taiwan’s capabilities were known.

As for Chang Hsien-yi, who became a Christian and enjoyed playing golf outside a part-time role at a nuclear safety consultancy firm, the decision he made four decades ago was correct.

“Maybe that’s good for the Taiwanese people. At least [we] didn’t provoke mainland China in a such way to start an aggressive war against Taiwan,” Chang said.

“I did it with my conscience clear, there is no betrayal – at least not to myself.”